|

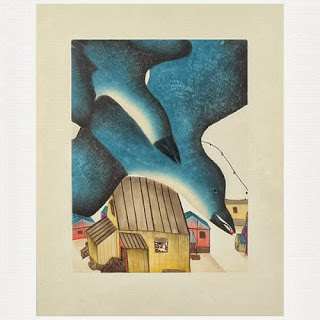

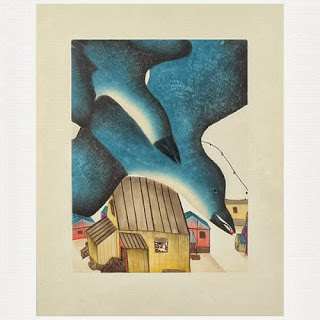

Kenojuak Ashevak, Serpentine

Wolf, 2013

Lithograph, 22 1/8 x 30 in.

(57 x 76.5 cm)

Printer: Niveaksie Quvianaqtuliaq |

While I have learned a great deal about Alaskan Yup'ik basketry over the last couple of years, it wasn't until recently that I began to read and learn about Inuit sculpture and prints. This month, the annual Cape Dorset Print Collection will be released. Ann B. Lesk, owner of Alaska on Madison, a gallery specializing in Northwest Coast and Northern Alaskan contemporary and historic art in Manhattan will be hosting a preview reception from 6 to 8 p.m. on Thursday, October 17. Lesk gives us a glimpse into this wonderful annual event that collectors all over the world look forward to in anticipation:

PN: For those people who don't know anything about Inuit prints, talk a little about the origin of the Cape Dorset prints, what they are and why they are so appealing to people.

AL: Cape Dorset is a community of about 1200 Inuit (Canadian Eskimo) which describes itself as the "Capital of Inuit Art." Every year since 1959, Cape Dorset has released a set of limited edition prints created by artists from the community. The first prints were stunningly sophisticated, especially when you consider that this was a new art form for the Inuit. The annual collections have shown a wide range, including exquisitely realistic portrayals of Arctic birds and animals, stylized fantasy compositions, social commentary, and shamanistic images. I think that they appeal to people because they combine sophisticated design with an exotic Arctic perspective. Cape Dorset prints originated through serendipity. James Houston was a Canadian artist who was living in the North and, since 1949, had helped to create a system of Inuit-owned cooperatives to promote and market Inuit art in the South. Initially, this meant soapstone and ivory carvings. Houston was talking with one of the artists, who looked at Houston's pack of cigarettes and commented that it must be very boring for someone to have to draw the same picture on each package. Houston took a walrus tusk that had scrimshawed engravings on it, applied ink, and showed the artist how one could make a print from a master image. This conversation led to experiments with printmaking in Cape Dorset. Houston went to Japan to learn low-technology printmaking techniques that could be used in the Arctic, and supervised the creation of a printmaking studio in Cape Dorset.

PN: How many prints are available for 2013 and how much can collectors expect to pay for a Cape Dorset print?

PN: October marks the opening of your Cape Dorset print show for 2013. How many years has Alaska on Madison offered these prints to collectors of fine Alaskan art?

AL: This is the second year that Alaska on Madison has offered the Cape Dorset Print Collection. We are the only gallery in the greater New York metropolitan area that exhibits the collection. The other American galleries with the collection are in Maine, Minnesota, California and Washington State.

PN: Who are some of the most famous Cape Dorset print artists of all time and who are the up and comers in your estimation? Do you have any particular favorites for this year?

AL: Kenojuak Ashevak (1927-2013) was undoubtedly the most prominent Cape Dorset print artist. Her death in January was a great loss for the Inuit art world. She catapulted to fame when one of her prints, "Enchanted Owl," was published on a Canadian postage stamp. She continued to experiment with new techniques right up to her death, and was an inspiration to generations of new artists. This year's collection includes seven of her prints. One, "Serpentine Wolf," is a new departure for Kenojuak, using lithography to introduce texture into the design. Recently, we also lost Kananginak Pootoogook (1935-2011). His elegant portrayals of Arctic wildlife were mainstays of the Cape Dorset collection for many years, along with astute graphic observations on the relationship between the Inuit and outsiders. The stars of the next generation are Ningeokuluk Teevee, who is represented by six prints in the collection, Tim Pitsiulak, who has three prints in the collection, and Shuvinai Ashoona, who was represented in last year's collection. This year's collection includes prints by three newcomers. The youngest is Saimaiyu Akesuk, age 27, who is the granddaughter of Latcheolassie Akesuk, one of the great first-generation carvers in Cape Dorset. Saimaiyu's prints include an explicit homage to her grandfather's work, Lacheolassie's "Birds," and her other prints clearly show the influence of his abstract style.

PN: For the first time Cape Dorset print spectator and perhaps purchaser, what tips do you have for buying pieces on the secondary market?

AL: The Cape Dorset Annual Print Collection is offered only through galleries and museum shops. Each print is signed, has a legend that indicates the year it was made, the impression number (e.g., 13/50 means that this is print number 13 of the edition of 50), the title, the print technique, and the community (Cape Dorset). Many prints also include a "chop," or stylized signature of the artist and sometimes also the printer. If you are buying older prints, be sure to look at the condition of the print carefully. Be sure to check the print technique (see below). For both old and new prints, you should find out what you can about the artist--whether they are well established or unknown, prolific, or represented by only a few works.

|

Ningeokuluk Teevee, Tulugak's

View, 2013

Etching and aquatint, 32 x 25

in. (81.5 x 63.5 cm)

Printer: Studio PM |

PN: What is the artistic process that brings Cape Dorset prints to life?

AL: The 2013 Cape Dorset Print Collection includes prints made using four techniques: stonecut, stonecut-and-stencil, etching-and-aquatint, and lithograph. The first Cape Dorset prints were stonecuts. As the name suggests, a flat surface was made on a large stone, the image was cut into it, inked, and printed. The second technique introduced in Cape Dorset was stencil or stonecut-and-stencil. In a stencil, a pattern is cut out of a mask, and ink is applied to the paper in the cut-out areas. Stonecut-and-stencil prints combine these two techniques. Lithographs were introduced next. Although lithography was originally developed using stones, as the name suggests, modern lithographs are made by applying ink to a metal plate that has been treated with chemicals. Etching-and-aquatints combine traditional etching techniques with hand-applied coloring.

The prints are frequently a collaboration between an artist, who prepares the design, and a printer, who cuts the stone, prepares the lithographic plate, colors the etching, or inks the stencil. The printer may make significant decisions that affect the appearance of the final print, emphasizing or downplaying elements in the artist's drawing.

The interaction between the print's designer and the printer can be seen in these pictures of the drawing and finished print for Kenojuak Ashevak's "Dog Sees Spirits." You can see that the print does not just follow the lines of the drawing; it smooths them, and even adds a little bird-like creature at the top right. The way that the ink is applied also enhances the overall esthetic effect of the print. These changes would have been discussed between Kenojuak and the printer, Kananginak Pootoogook.

|

| 1960 Pencil Drawing of Kenojuak's "Dog Sees Spirits" |

For a link to a film about the process of making Kenojuak's "Arrival of the Sun" click HERE.

|

| 1960 Print of Kenojuak's "Dog Sees Spirits" |